Sermadurai quietly pushed the big iron gate of Kannayiram’s house and peeped in through its gaps.

The horse couldn’t be seen.

Only an Innova parked along the building wall showed up in his line of sight. Craning his neck further, a few flowering plants and a bike could also be spotted.

Not sure where the horse was tethered, though. Yesterday evening, Kannayiram’s men seized his horse as lien for a loan he had taken from him.

Sermadurai wasn’t home then. After the horse carts stopped plying in the town, he lived on running errands for a pushcart vendor of soups and mushrooms in the evening. It got him ten rupees a day, and dinner.

His noon hours went by on odd jobs like hawking guava or ice cream from a push cart. He had no idea how he was going to be able to repay the twenty thousand rupees loan with such meagre income. In fact, twice the loan amount has already been paid as interest; and interest for three months is overdue. So, the lender seized the horse – his only asset.

To hell with it! Sermadurai spent his night at home swollen with ego. But his mind soon got restless. Would they have fed grass for the horse? It has a sore on its ear, doesn’t it? He was worried if they would have dressed it and applied an ointment.

If he went to check on it now, instead of the horse, he could be held hostage by Kannayiram’s men. That very fear tied him down to the house all night.

However, once it was dawn, he could no longer hold himself together. He set out to see the horse, picked up a few regular herbs on the way, crushed them to a paste and bundled it in a small rag cloth. He was sure Kannayiram would not be in his house after 9am. He would always be at the gas station. In fact, Sermadurai took his loan from there. He had been there a few times earlier to pay his interest. Kannayiram owned four or five gas stations. Plus, a cinema hall and a lodge.

When he was running his horse cart in those days, Kannyiram was only a sales boy at some grocery store. Time had elevated Kannayiram and plunged Sermadurai down.

He has been plying the cart for more than twenty-five years. He had a different horse before. A white horse. One should be lucky to get one such, they said.

He bought it from Vasireddy in Nellore. Thank the horse, his stars or whatever, he was soon flush with money. During such prosperous times, his folks kept advising him to marry his cousin. Sermadurai paid no heed to anybody.

He brought “New Street” Saroja as his live-in partner. Though slightly dark in complexion, her physique was smooth and luscious like the tender shoots of coconut. He kept giving all his earnings regularly to her. His meals used to be like a king’s spread – ghee rice, mutton curry, fish, quill and dried fish, which he ate with great relish. He spent his leisure hours and days at cinemas, temples and holidaying in Kodaikanal.

All this dried up in a few years. Penniless, he was forced to sell his white horse. Even that money went to Saroja. One fine morning, Sermadurai found Saroja and her possessions gone.

He was stung with pain when he learnt that she had eloped with a certain person in Veppankulam. He was cooped up in the house for a couple of days. When hunger pushed him hard, he started moving about. Bought a new horse from Andhiyur bazaar after borrowing some money from Kannayiram. Devanai, the horse that he has now is indeed that one.

He had elaborately decked it up in all its fineries with bells, beads and beautiful blinkers. A sight to behold! But with the gallop of time, everything withered away.

Devanai is the last remaining horse in town now. He hardly takes his cart out as no one hails a horse cart anymore. Occasionally, he lends the horse for wedding festivities. Frail with age, no one even cares to enquire for his horse nowadays.

He contemplated selling it. But who would buy an old, worn-out horse? He was saddled so much with debt that he couldn’t even afford to look after it well. There was a time when he fed the horse with nutritious feed like oats, barley and wheat bran. Now, it is only grass and leftover leaves. A wound in its ear, aggravated by puss, has drawn a permanent swarm of flies over its face. What a poor creature it is, he felt.

****

He noticed a servant emerging from the house with a woven basket in hand. He wondered if he must hide or ask him about the horse.

Sermadurai respectfully folded his hands to greet him when he came out of the gate.

“What do you want? Why this meek look?” the servant asked with a frown.

“I am the horse cart fellow. Your men have taken away my horse”.

“Oh, that sick-looking horse? It has been given away to the slaughter house along with the old bulls”.

“What do you mean! Sent to the butcher?”

“What… should we take it to a pageant? He bought it for five-hundred rupees”.

“When?”

“About six o’ clock. You know there is a tin factory towards the west, don’t you? The lorry would be leaving from there. Go, see there”.

On hearing this, Sermaduarai’s hands and legs trembled. He walked as fast he could towards the factory. His eyes welled up with tears as though reading his mind.

A life that gifted me years of livelihood. It is unjust if I allowed it to be killed – so saying, Sermadurai gathered pace.

He was filled with rage about Kannayiram. Unthinkable that someone could do this for some measly money. “Scoundrel”, cursing him, he walked towards the tin factory. The road would rise like a mound. In his riding days, the horse bore the weight with its legs. It had to be nudged to move ahead. Today, he walked gasping hard for breath.

Cows – starved, frail and gaunt – were being pushed into the lorries parked in front of the factory. The horse was not to be seen. “Would they have taken it in another vehicle?”, he grew anxious and asked the lorry cleaner.

“Of what use is that? I have tied it up there”, the lorry cleaner answered.

It was standing behind the building. The puss oozed from its ear. He went near it, stroked the horse, cleaned its ear with a piece of paper from the ground. Its eyes were dry. He kept speaking with the horse while gently rubbing his hands on its forehead.

He saw the meat trader, smoking a cigarette, coming towards him.

“Yei, who are you? What are you doing here?” he asked in a raised voice.

“My horse…. saami”, Sermadurai dragged his voice.

“I have seen you, I say. Are you not the same fellow outside the railway station with the horse cart?”

“Yes, ayya”.

The meat trader could recognise him.

“What did you say your name was?”

“Sermadurai”.

“You used to have MGR’s picture pasted in your cart. I remember”

“Yes, saami. MGR is dear to me like my life”.

“I have once travelled in your cart. You offered me a lift in your cart once when I was going to school. Do you remember?”

“Can’t remember, saami”.

“Who travels by horse cart nowadays? We have minibuses and autorickshaws.

Anyway, how did the horse go to Kannayiram?”

“He took it away because of my loan”.

“What will you do with this thing?”.

“I have cared for it like my own child”.

“I bought it for five-hundred rupees. Who will pay me that?”.

“I will, sir. Please give my horse”.

“Can you sing an MGR song?”

“Yes, I can, saami”.

“Okay, now sing Nenjam Undu, Nermai Undu, Odu Raja (I have a heart. I have an integrity, Gallop, my King). I will release your horse”.

With a broken voice, he sang Nenjam Undu, Nermai Undu, Odu Raja. The meat trader also sang along with him. Sermadurai ended the song with a cough.

“Why should I carry your sin? Get lost… take it way”, saying this he threw the cigarette down and stubbed it out with his foot.

“Thank God, I got my horse”. He escorted the horse through the blazing sun and returned to his house.

****

Sermadurai lived in the only, lone house near the foothills of Arali Hills in the west. A sirisa tree stood outside the house. This used to be a warehouse for matchboxes in the past. Fireworks Chellaiah’s family had allowed him to stay on because of his many years of acquaintance with them.

Years ago, ten to twelve horse carts used to be lined up neatly in a row outside the railway station. The train passengers would pick a “well-dressed” cart from among them. Sermadurai had spread out a big carpet in his cart, and kept a hand fan made of palm fronds for passengers. A small box of betel leaves for him. Plus a few peacock feathers for added decor. Yet, Sermadurai never demanded high wages. No wonder, it was easy for him to find customers.

His horse cart was the first choice for anyone. Apart from railway station, temples and cinemas, there were regular trips to Dr.Chellaih’s house. Everybody from the family of Timber Mills Kandasamy Mudaliar or ex-Chairman Karaiyalar always asked for his cart. They treated him like they would one of their family members.

They had such faith in him that they would, without a worry, send their womenfolk alone in his cart.

Timber mills Kandasamy believed a lot in astrology. He had a habit of meeting a couple of new astrologers every week. On those days, he would leave at the break of dawn in Sermadurai’s cart. Kandasamy Mudaliar would always have his breakfast at Abhirami Mess, which was adjacent to the railway gate. Ate only idli & vadai. He would urge Sermadurai also to eat along with him.

“What you do is a hard job, eat some more”, he compelled him with concern while gesturing to the waiter to bring a few more idli.

“Let me tell you something, Sermadurai. Never starve ever. Always eat on time. That’s why I have been urging you to marry, but you wouldn’t listen”.

“Why marriage and all for me, sir”, Sermadurai refused.

“Can I look for a girl? A family known to me in Kadayanallur has one”.

“Please no, sir. It is sufficient if I could put just about enough food on the plate for me and my horse”.

“You can’t keep living like this forever. What if you take ill someday? Wouldn’t a girl at home be helpful?”

“Let this plight end with me. I shouldn’t be the cause of a girl’s misery”.

“Incorrigible fellow you are. Whenever you are not well, simply head to my house. I will look after you”.

“Your words mean a lot, sir. God bless you”.

“My wife is very bighearted. She wants to see ten or twelve people fed well in the house every day. You know her well, don’t you? Generous to a fault… doesn’t think twice about even offering her bangles & necklaces if someone comes for help”.

“Like husband, like wife. The heart that gives always stays rich, sir”.

“What is there to hide from you? None of the businesses I did before marriage worked out. Only after her coming did my business get better. Built a new house. Started a timber mill. I owe it all to her – she is my lucky charm. She came from a family of modest living. But she brought along with her Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth. It is pouring money for us”.

“God bless her, sir”.

“She has the last word in everything… just no second thoughts for me”. Kandasamy Mudaliar is always like this. Speaks his mind openly. Keeps nothing close to his chest.

He has engaged my cart a few times to visit temples with his wife. Each time, she has paid me more than what was agreed upon.

Two years later, Kandasamy Mudaliar launched a bus service. It did not do well, belying his expectations. A couple of accidents also happened.

One day, he went to meet an astrologer in Pudur in his cart.

“As per your horoscope, you will incur loss. Sell your bus transport company at whatever price it fetches”, the astrologer read out his predictions. Kandasamy Mudaliar turned a deaf ear to his warning. Owning a bus transport business was his wife’s desire and he fulfilled it by starting it. He swore by his wife’s luck. Can any ill-fate come near his strong lucky charm?

On his way back, he began a tirade of abuses against the astrologer that continued till he reached home. However, things eventually proved the predictions. Successive damages in the form of fire and loss. Huge debt. The relatives squarely blamed his wife – his lady luck – for all the misfortune. Yet, amidst all this, he did not utter even one word of anger at her.

She herself once told him, “It is wrong to have gone by my suggestion. All gone… now we are deep in debt”.

“Don’t say that, dear. It was an unknown trade. Let down by those whom we trusted. What can you do about it? You are Swarna Lakshmi (Goddess of wealth in gold). A person with Midas touch”.

She did not reply. But she let out a loud wail. In the following two weeks, Sermadurai heard that

Kandasamy Mudaliar was planning to sell his house. At this, he shed tears.

Kandasamy Mudaliar asked Sermadurai to take him to meet a certain advocate. Midway through the journey, Kandasamy Mudaliar asked him to halt for a while and said, “I can’t live in a rented house after having lived in an own house. It would be a big embarrassment for me. Planning to shift to Coimbatore with the whole family. This will be my last trip in your cart”

“Please…. don’t say that, sir. Difficulties come for everyone. For a good-hearted man like you, things will surely get better”.

“I have lost all confidence. Two girls of marriageable age at home. Don’t know how I am going to get them married. Can’t sleep in the night. Burdened with worries all the time”.

“How could you speak like this, sir”, said Sermadurai, wiping his tears overcome by emotion.

When returning from the advocate’s house, Kandasamy Mudaliar did not speak even a single word. His face was dark.

The next morning, Sundaram ran to Sermadurai and announced, “Kandasamy Mudaliar has committed suicide”.

“When was it?”

“Early morning”.

Sermadurai’s legs trembled when he stood outside that house. What a good man he was! Gone like this. Seeing the women lamenting, even he couldn’t control his emotions.

So many great men like Kandasamy Mudaliar have passed away. Famous families of the town have vanished. All and sundry have now become the town’s new rich. New buildings have come up after pulling down old shops and houses. Familiar faces are getting fewer. Only the town’s name is unchanged.

With all these changes, the horse carts too faded into history. Autorickshaws stand where the horse carts once stood. No more sounds of gallop on the road.

Sermadurai continued to ride the lone, last horse cart in town. As a transport vehicle to hospitals for old people, as a publicity vehicle for textile shops snaking and screaming through the streets and lanes – he did just about any work that came his way. With each passing day, his earnings kept dwindling. After a full day of zero income, he parked his cart by the Gandhi statue in the night and began ranting and raving. With none else in sight, and clueless who he was shouting at, the street dogs ran in fright. After that, he never took his cart out.

On some days, he considered running away to somewhere in North India. It was his confusion over what to do with the horse that held him back.

****

He made a medicine, applied it on the horse’s ear and covered it with a cloth. Its eyes bared a look of pleading for something. For what did I rescue this horse? What maybe done with this? He was totally clueless.

The horse would anyway die in a few days. I don’t have the heart to see it going. To keep it alive, I need money. But I have none. Unable to sleep, he spent the whole night thinking about all this.

Riding the horse cart gave him so much joy in those days. There was not a street or lane he hadn’t ridden through. The transistor in his cart multiplied his joy – the only cart in town to boast of one. It played movie songs. He would happily ride listening to them. The distinct sound of his cart returning home could be heard clearly in the night.

Everything is gone. Those good times won’t come back. Why should I stay in this town when all those who loved me have long left the world? Why is the town possessing him?

He remained confused all night.

Early morning, when it was still quite dark, he descended the slope and walked till the bypass road. He hailed a lorry that was heading North.

“Where to?”, the lorry driver enquired.

“To Tirupur”.

“I am going to Salem. Will you change over to another vehicle if I drop you mid-way?”.

Sermadurai nodded his head.

The lorry sped past tearing through the breaking dawn. The driver stopped the lorry by a wayside restaurant at 8 a.m, and got down to eat.

Sermadurai did not have a rupee on him. So, he stayed put in the lorry hesitating to go with him.

“Come, let us eat”, the driver invited Sermadurai.

“Not hungry”, Sermadurai refused politely.

“I have the money, come down”, said the driver. Sermadurai shrank with shame when he heard this.

When they sat down to eat, he remembered the horse tied outside the house.

“Going in search of a job”, the driver asked.

“Yes, no work for even one square meal in my town”.

“What work were you doing in your place?”

He did not reply. He blankly looked at the leaf. The waiter placed steaming hot idlis for him. When he took a piece of it to his mouth, he felt overcome by guilt for leaving the horse in the lurch.

“What are you thinking about? Eat, I say”, the driver urged.

Its infected ears and dry eyes flashed across his mind and thronged him hard.

“Tongue tastes bitter”. Unable to eat even a single piece, Sermadurai got up and walked outside.

As though washing his hands, he bent down and wept.

Pity! After all, Sermadurai can afford only that.

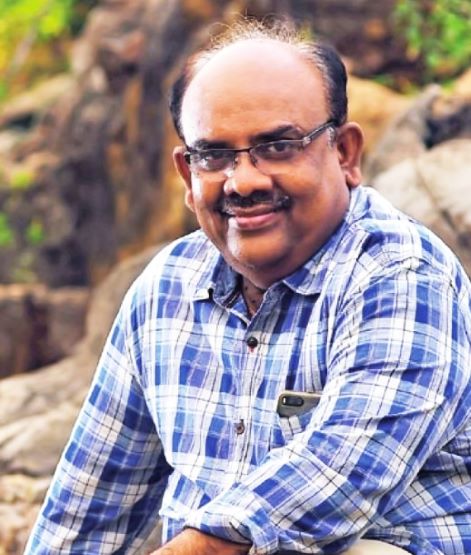

S Ramakrishnan is one of the most prolific and celebrated writers of modern Tamil literature. His vast body of work spans fiction, plays, screenplays and essays. He has written and published 11 novels, 55 collections of essays on world cinema, world literature, Indian history and paintings; 20 anthologies of short stories, three plays and 21 books for children. He has received many major awards for his literary works, including the Sahitya Akademi Award in 2018, Tagore Literary Award and Maxim Gorky Award. Sancharam, the novel which won him the Sahitya Akademi award, is a poignant portrayal of the lives of Nadaswaram (a wind instrument) artists – an instrument that is a part of all celebrations but not the artist who plays it. His short stories and essays have been translated and published in English, Malayalam, Hindi, Bengali, Telugu, Kannada and French.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates