His hands were tied behind his back. In the enormous distance around him, he noticed cold air enter and descend gently, covering the earth with the whiteness of dew. The mist changed the character of everything— even the houses. It filled the bricks with passion, seeping through the cracks in the roof tiles. From the playground, he saw the three streets diverging into the village. He was alone, with only two trees for company; his wrists tied around one of them. His lips cracked as the mist enveloped him. A sleep-deprived turkey wandered the playground and yelled kawak kawak, creating a commotion in the streets.

Only after midnight did the moon reveal its face. The night dragged on without end. He could not free his face from the hair that fell across it. Above him, the fruits of pungai1 trees hung like locks of hair. The aroma of these fruits permeated the streets and lingered as if they had a mind of their own. All the windows of the houses were shut. The sky moved, its blueness darkened and burst into serene blackness. He clung to the tree like bark, while the fingers of the leaves moved constantly. He stared at his feet, suffering as moist air seeped into open sores on his body. The ground reverberated with the sound of wind tearing into a broken straw box. He could hear the groans and the coughing of some elderly people.

Two ants descended from the tree and wandered on his body after resting blissfully beneath the pungai flowers. They scaled his forehead with their black shredded abdomens and, frightened by the new landscape, stumbled down and moved about aimlessly. They dashed across his face, went into his ears, descended to his shoulders, and then scurried back to his face. He had never before observed an ant up close and relished the way the ants gripped his whole body. His face contracted and expanded involuntarily, as they with their little legs, crawled across pushing and pulling his skin. Without a clear way forward, they ran back to the branches of the tree.

***

He walked the same way, gripping the wet roof tiles cautiously a few hours earlier. There was already a chill in the air. He spotted the pumpkin vine that burst into blooms while he traveled towards the western bend and leaped from one wall to the other. The pumpkins abandoned by people in that late winter were protected by their foliage. Dogs slept soundly with their faces buried in the sand. As he walked along the walls, he took a sharp knife out of his hip and sliced the vines. Without chickens to peck on them, sopped grains in the backyards were rotting away. He saw his face in the reflection of the stars in the little tub’s quiet waters. He descended into a stable covered with sacks and tarps.

When the cows woke up from the noise, he instantly climbed to the roof through the keystone. He gently stood up, looking out the window at the church’s stained-glass windows, the bell tower, and the pungai trees. He cast a quick peek over the roof tiles to check if any pigeons were trapped inside. They would creak if he walked on them. He’d get caught. There were no pigeons in the hole filled with sawdust he inspected. He found a sparrow’s egg instead and sat on the roof tiles mindlessly without fear.

In the house underneath him, there were only women. They lent money and the men in the house went out every month to collect the interest. He knew that when he chose that house.

He looked into the house through the only glass tile on the roof and saw the dark floor. There was a lamp in one corner of the house and the light came to the floor in waves. He could easily enter the house if he could take out one of the tiles on the east side. It was firmly lodged in; he used his knife to push it but he ended up smashing the tile. He noticed a cat jump from the adjacent roof and begin to stroll with him as he lifted the shattered pieces. It looked up at him with its tail curled up. The cold air began to flood the house through the hole. The lamp’s light was extinguished. When he tried to lower himself into the house, by clutching onto the wet tiles, he broke them again. Before he could hoist himself back to the roof, he tumbled inside the home with the sound of numerous shattered tiles. The women woke up.

The oldest sister went screaming into the streets through the front door. Before the street could become overrun with noise, he made an effort to flee. Someone threw a crutch stick aimed at his legs and his legs gave in. The howls of the dogs and infants who were woken up by the ruckus began to reverberate throughout the streets.

An old man’s fingers clutched onto his hair. Some arrived carrying hurricane lamps and stood far, restless. The oldest sister had tumbled into a chicken coop in a hurry; the scattered chicks started pecking for food without any knowledge of what had happened. He squeezed his eyes shut when someone lit a matchstick and held it up to his face. They had no trouble recognizing him and he received a tight slap. The women arranged their undone sarees, still partially asleep. The normally sleepy blind man woke up and approached the scene as they pushed the thief by his nape into the playground to tie him up on the pungai tree. The blind man’s voice had the same screaming quality as that of insects at night. He reprimanded the sleeping dogs for not having done their jobs properly, as he drew nearer.

Everyone believed that the blind man was loaded with gold and cash and that he had hidden them in his mattress. He was usually asleep but when he spoke, he spoke bitterly. As he came close, the blind man’s fingertips pressed into and moved about the thief’s face like little sandworms, and he scolded him in between deep sighs. And when the blind man left, they paraded the thief behind him to the playground and tied him up to the pungai tree.

He looked at one of the girls who was hiding behind her mother. She berated him to her mother as her face was shielded by her mother’s saree, “look at the bloody thief, gazing at me.”. On the stone next to the tree, two boys observed him intently. They had never associated such a lanky, sunken-cheek figure with a thief. He bent down with his hair spread across his face. The boys discussed accompanying them when they escorted the thief to the police station in the morning. The crowd dispersed a little. After chasing the boys to their homes, an old man sat on a stone smoking a cigarette. When the women of the house retired with exhaustion, he saw someone in the crowd who looked like his wife. It seemed to him that it was going to be a long night for everyone; so much to talk about until they fell asleep.

Cigarette smoke circled his face and penetrated his tongue. He took a deep breath in and then held it as if he had captured a small amount of air for himself. His wife would have been asleep at home by that time. Despite her yearning for children, she was unable to become pregnant for eight years. Like a little girl, she went from house to house with her tiny eyes, grinding items on a quern. And for some reason, he recalled the dried pine flower that she kept in her box.

The shock prevented the town from sleeping. The two ants occasionally walked up and down his head. Under his feet, he could feel the dew settling. No birds were seen visiting the tree.

For safety, they discussed placing one person on the playground. They hadn’t forgotten the thief who had been apprehended and restrained many years earlier and whose lips had cracked as he died in the cold. The tree in which he was restrained was no longer there. The women had requested it to be cut.

The dead thief moaned and screamed hysterically all night. At many points, it seemed as if he would uproot the tree with him. At moments, he spoke to himself. Everything was the same. Winter. Deserted streets. A thief. He cursed the cold all night as if that would exorcise it. When he was done cursing, the streets were filled to the brim with mist. His body remained there for three days. People who marched towards the south in hopes of finding some identification had come back empty-handed. He had a tattoo of a scorpion on his back. Since they could not find who he was, the people of the village themselves cremated his body. The village experienced a severe drought the year after the cremation and scorpions appeared at random in many homes. For many years, the women recalled the bent knees of those scorpions.

Only now did they catch another. The person who was made to stand guard couldn’t stand in one place. He cracked his knuckles all night and wore a ring that looked like a snake. Sometimes, he came close to the thief and lifted up his hair to see if he was still breathing. When the cold was becoming unbearable, the guard went back home leaving the thief to face the night all by himself.

The more he stayed awake, the worse his hunger and thirst became. He could not help but think about the small boys and how they would not be sleeping that night.

***

As a child, he had always preferred to stay up and travel, rather than sleep. And when he wanted to sleep, he would try to sleep in the open spaces, on wild terrains, on the steps of the temple, or on top of heaps of paddy straw. Ayya was the same. When the nomadic shepherds set up their pens in open fields, Ayya would stay with them at night. The thief would accompany them. And when he slept with the shepherds, he dreamt wildly, most magically.

The shepherds were afraid of Ayya. The food that they ate together tasted different in the wild. In the moonlight, Ayya traced the squares for 18 tigers and goats2 on the ground. The Sivakulam shepherd stepped up when the other shepherds were too terrified to play with Ayya. Tigers for Ayya. Lambs for the shepherd. Ayya’s tigers did not touch a single lamb and the lambs trapped his tiger in a corner again and again. The Tigers were trapped in seven consecutive games and the shepherd kept on winning. During the eighth game, the shepherd gazed into Ayya’s eyes by chance and noticed that they were hostile and aggressive, like a tiger’s. He purposefully cleared a path for the tiger to slaughter his lambs. Ayya grew incensed and yelled, “There’s no reason to give up and let me win!” The shepherd stopped playing the game and began brewing coriander coffee instead when only one caged tiger remained.

In the distance, the lambs stood motionless, staring at the ground. Ayya saw the imprisoned tigers. Some of the partially burned straws leaped out of the flame as a fireball crackled and erupted. Spectral shadows appeared and vanished. The air was thick with the pungent fragrance of coriander. Even after drinking the steaming coffee, Ayya lost the game. Amid the lambs, the shepherd found slumber. Ayya and the thief were sprawled out on the ground near the squares. The stones that had played the part of tigers were once again back to being stones. Ayya rolled on the floor and fell asleep.

The shepherd observed the sheep’s sly, slinking form. With a knife in his hand, Ayya crept through the flock of lambs and went over to the shepherd. The lambs twisted their bodies to make way while rubbing their snotty noses on him. As Ayya came close and stood up, the shepherd shooed the lambs away. Ayya put the dagger back on his hip. While pretending to ask for a matchbox, Ayya asked the shepherd if he was up for another game. He knelt at Ayya’s feet and begged for forgiveness, saying, “If I have offended you in any way, please do forgive me. I am simply here to survive.” Ayya remained with him while he talked about his family till morning. The thief enjoyed the scent of lambs’ milk that permeated the air.

The cigarette smoke vanished. He hunched over and leaned against the tree. The surrounding tree, buildings, church, and turkey became invisible as the mist began to spread. Leaf by leaf, it fell to the ground, and the cold tree stood still. He shut his eyes as moisture seeped into the barkless tree quickly.

The chicken trapped in the mist cried. He was weak. He felt that he had slowly gotten inside the tree and that all the other branches were just sprouting from him. The knots in the tree trunk, the cracks, and the fact that the tree couldn’t move gave him more grief. He felt like his hands above him, untied, constantly moving.

He felt the tree’s nourishing juices stream through his body and felt protected. The tree had grown in all directions. Due to its height, it could be seen throughout the entire village. Thousands of leaves and pods looked weird when he looked up. He suddenly recalled going hunting while covered in pungai leaves.

He used to go hunting with Ayya. Pungai leaves would be pinned to their bodies and heads. When they returned from the hunt, the blood of the slaughtered chicken they brought back would be splattered all across the street.

The sky looked like it was splattered with a turbid pool of blood. His body was trying to drift off into a deep sleep. At some point, he did fall asleep. And then, he couldn’t remember anything. He woke up when the heat stroked his body.

***

The two boys were sitting opposite him. One of them had his knife. He was threatening the others by dangling it in their faces. The ground brightened and the tree stood tall and proud as if it had expelled him out of its body. The town was transformed. . The men who had come to fetch him had bathed and sported perfectly combed heads. As they spoke, they looked up at his head resting on the tree.

“He is so weak. We have to give some kanji before taking him.” One of the boys ran and quickly returned with water in a small pot and some rice porridge. He was nauseated and couldn’t drink. Women scared their young children by pointing to him. It had become warmer. The faces he noticed in the darkness had all changed into something else. The dogs chased after him barking as he was led down the street. Once, when he was ready to cross the street, he turned around to look at the playground.

The tree was standing solitary under the sun. The two ants which had not been able to find their way down the tree at night had managed the descent without any trouble. When they reached the spot where his head had once rested, they stopped in fear and began to crawl. By the time, the thief and the others left town, the ants realized that the tree had taken a new form. They descended quickly to the ground. The sun was at its zenith.

(first published in a special 1992 Tamil issue of India Today)

1 Also known as pongam or pungu. Known in English as the Indian Beech or Pongamia oiltree. It is popular for the medicinal benefits of its fruits, seeds, and oil. Many local communities believe that it brings good health when planted near the house.

2 Part of a game called aadu puli aattam (Lambs and Tigers) – a strategic two-player game popular in South India. One player controls 3 tigers and the other 15 lambs/goats. The tigers ‘hunt’ the lambs and the lambs try to surround and block the movements of the 3 tigers.

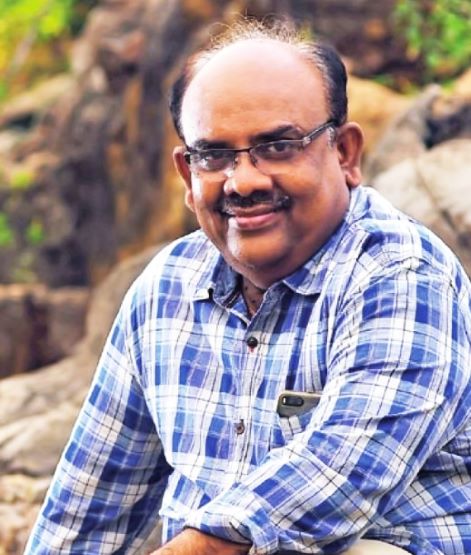

S Ramakrishnan is a Sahitya Akademi award winning Tamil writer. He has written 9 novels, 20 collections of short stories, and 3 plays in fiction. He is also a translator and scholar who has written treatises on a variety of topics including painting, history, world literature and cinema. His short stories have been translated into English, Malayalam, Hindi, Bengali, Telugu, Kannada and French. He has received numerous awards and recognitions for his contributions to the literary world over the last 25 years.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Usawa Literary Review © 2018 . All Rights Reserved | Developed By HMI TECH

Join our newsletter to receive updates